Fundamentals of Electron Microscopy

Recall the De Broglie wavelength, \(\lambda = \frac{h}{p}\), where \(p = mv\).

In TEM the electron momentum is given its momentum by accelerating it through a potential drop \(V\). The potential energy must equal the kinetic energy.

\[e V = \frac{m_{0} v^{2}}{2}\]Solving for \(v\) and making use of the momentum definition:

\[v = (2 eV / m_{0} )\] \[p = m_{0} v = (2 m_{0} e V )^{1/2}\]Note the inverse relationship between \(\lambda\) and \(V\). Accelerating the voltage decreases the wavelength of the electrons! In non-relativistic cases (\(< 50\) keV), the wavelength is given by:

\[\lambda = \frac{h}{(2 m_{o} e V)^{1/2}}\]Applying the relativistic correction (\(> 50\) keV or \(1 \%\) of \(c\)):

\[\lambda = \frac{h}{ \bigg[ 2 m_{o} e V \big( 1 + \frac{eV}{2 m_{o} c^{2}} \big) \bigg] ^{1/2}}\]where \(m_{o}\) is the rest mass of the electron and \(e\) is the electronic charge.

In both scenerios, higher energy electrons leads to shorter \(\lambda\), thereby increasing spatial resolution.

For context, visible light has a wavelength of about \(\lambda \approx 500\) nm. Electrons with an energy of \(100\) keV has a wavelength of \(\lambda \approx 4 \times 10^{-12}\) m, providing a resolution of about \(10^{-10}\) m, which is the intermolecular distance.

Electrons are capable of removing tightly bound inner shell electrons by transferring some of its energy to individual atoms in the specimen. This is called ionizing radiation, producing a wide range of secondary signals. In no particular order:

Secondary Electrons

Back Scattered Electrons

Auger Electrons

In/Elastically Scattered Electrons

Bremstrahlung X-Rays

Characteristic X-Rays

Visible Light

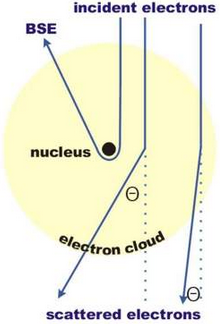

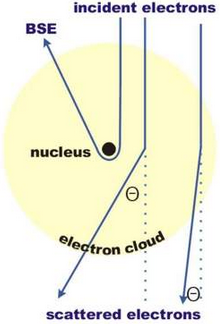

Elastic scattering refers to the electron interaction with a nucleus (and electrons) of an atom where no energy is transferred (although the it’s direction might change). An electron traveling into an electron cloud of an atom experiences the Coulombic Force:

\[F_{C} = \frac{Q_{1} Q_{2}}{4 \pi \epsilon_{o} r^{2}}\]The electron’s path is deflected towards the core as a result of Coulomb interaction. The scattering angle of is proportional to \(F_{C}\) and inversely proportional to the distance to the nucleus, \(r\). In other words, low scattering angles is a result of Coulomb interactions with the electron cloud, whereas, high scattering angle or back scattered electrons (BSE) come from Coulomb interactions with the nucleus. This is also known as Rutherford scattering.

Incident electron beams pointed directly at a thin sample will present a different contrast depending on the material. More specifically, The intensity of the direct beam decreases with increasing atomic number. For a homogenous thickness, areas with heavy atoms appear darker.

Inelastic scattering occurs when an electron transfers energy when interacting with a nucleus. An incident electron ejects a bound electron and scatters with an energy lowered by the electron bound energy. The electron experiences Coulomb interactions with the nucleus and can ionize the atom. It is also possible for Bremstrahlung radiation (in the x-ray wavelength) to occur.

Electrons that have been ejected are called secondary electrons and have low energies ranging from \(5 - 50\) eV. These electrons carry information on the surface topography.

Phonons are quanta of elastic waves, in other words, atomic vibrations in a solid. A primary electron can lose energy by exciting a phonon and effectively heating the solid slightly. Although a primary electron can lose a negligible amount of energy (as in about 1 MeV) by exciting a phonon, there are two ways phonons contribute to scattering effects.

All electrons that remain in the sample are likely to excite a phonon eventually. This is how the electron beam heats up the sample solid.

When phonon scattering occurs, the scattered electron is generally deflected at a large angle (~ 10 degrees)

“A plasmon is a wave in the ‘sea’ of electrons in the conduction band of a metal.”