Important Theorems and Equations for Special Relativity, intended as a review for Classical Mechanics and Electrodynamics

\(\let\vec\mathbf\) \(\newcommand{\v}{\vec}\) \(\newcommand{\d}{\dot{}}\) \(\newcommand{\abs}{\rvert}\) \(\newcommand{\h}{\hat}\) \(\newcommand{\f}{\frac}\)

Recall that an inertial frame of reference is a reference frame that is not undergoing acceleration.

Maxwell’s equations for electromagnetism were inconsistent with Newtionian physics in that it uses a universal constant ,\(c\), the speed of light, which says something about inertial frames of reference. Einstein came along and assumed Maxwell’s theory was correct.

Consider two frames \(S\) and \(S'\), with coordinate axes aligned:

\(S (t,x,y,z)\) \(S' (t',x',y',z')\)

\(S'\) move relative to \(S\) in the \(+x\) direction at speed \(v\). In Newtonian mechanics, these two frames are related by Galilean transformations:

\(t=t'\) \(x=x'\) \(y=y'\) \(z=z'\)

These transformations follow Newton’s second law, \(\v{F} = \frac{d\v{p}}{dt}\), where the applied force and momentum are invariant, \(\v{F} = \v{F}'\), \(t = t'\), and \(\v{p} = \v{p}'\).

Let \(u\) and \(u'\) be the velocity of a particle as measured in two frames moving with relative velocity \(\v{v}\) then:

\[\v{u}' = \v{u} - \v{v}\]1) The laws of physics are the same to all inertial observers. Moreover, if \(S\) is an inertial reference frame and \(S'\) is a frame that moves at constant velocity relative to \(S\). Then \(S'\) is also an inertial reference frame.

2) The speed of light is the same to all inertial observers.

A formulation of physics that explicitly includes these postulates is said to be covariant. Since \(c\) is the same in all frames of reference, \(c\) can be used as a conversion factor between them.

To satisfy the postulates , we intoduce a geometric framework called spacetime.

\[(\Delta s)^{2} = c^{2} (dt)^{2} - (x)^{2}\]where the interval is defined between points \(\v{A}\) and \(\v{B}\) is the time interval and \(x\), the space interval.

The relative signs chosen for space and time is such that real bodes moving at velocities less than the speed of light have \((ds)^{2} > 0\), which makes \(ds\) real for bodies moving slower than the speed of light. In other words, the interval can be described by:

\((ds)^{2} > 0\), timelike interval

\((ds)^{2} < 0\), spacelike

\((ds)^{2} = 0\), lightlike or null

For moving bodies,

\(v > c\), are called tachyons

\(v < c\), are called tardyons

\[(ds)^{2} = (cdt)^{2} - (dx^{2} + dy^{2} + dz^{2})\]Intervals defined by this equation exist in Minkowski space

Assuming Einstein’s postulates are true, let us investigate the second postulate. Consider two reference frames, \(S\) and \(S'\), moving relative to each other with velocity \(\v{v} = ( v, 0, 0)\).

Galilean transformations allow us to switch between reference frames:

\[x' = x - vt\] \[y' = y\] \[z' = z\] \[t' = t\]As it turns out, this is acutally not sufficient. In frame \(S\), the light ray traces out \(\f{x}{t} = c\). In frame \(S'\), \(\f{x'}{t'} = c - v\). This violates Einstein’s second postulate. To correct for this, we need to abandon the assumption that time is absolute. Time ticks at different rates for observers sitting in different inertial reference frames.

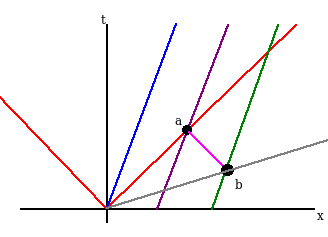

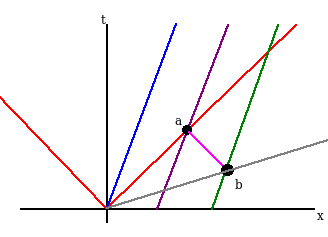

The red line is the motion of the light ray with equation \(x=ct\), setting \(c = 1\), we can reexpress this as \(x=t\).

Three observers are on the diagram, with their light motion diagrams colored blue, purple and green, seperated by one “space unit”. In other words:

blue: \(x = vt\)

purple: \(x= vt + 1\)

green: \(x = vt + 2\).

The blue observer and the stationary observer both agree that their clocks are \(t=0\) at the origin. The scenerio here is to find \(t=0\) for the purple observer, where does green have to send out their light signal such that the signal arrives at the same time as purple recieving blue’s signal?

Line \(\v{ab}\) denotes the light signal between purple and green. Notice that the \(\v{ab}\) is sent out such that it is perpendicular to the light ray and point \(b\) occurs above what the stationary observer calls \(t=0\), we’ll denote this time as \(t' = 0\).

So to remind us of the scenerio again: Obeservers blue and green are sending out a light signal to the central obersver, purple. The light signal arrived at the central observer at the “same instant of time”. The excersize here is to figure out the coodinates of point \(b\), since it is synchronous to the origin.

Since point \(a\) lies on \(x=vt + 1\) and \(x = t\) we can write two equations as a function of \(v\):

\[t_{a} = \f{1}{1-v}\] \[x_{a} = \f{1}{1-v}\]To find the equations for line \(\v{ab}\), that line can be written in terms of \(x\) and \(t\) as:

\[x + t = \f{1}{1-v} + \f{1}{1-v} = \f{2}{1-v}\]Now one more step… find the intersection of line \(\v{ab}\) with \(x = vt + 2\). We can simply rearrange this equation yields:

\[x + t = \f{2}{1-v}\] \[x - vt = 2\]Solving these two equations simultaneously:

\[t_{b} ( 1 + v) = \f{2}{1-v} - \f{2(1-v)}{1-v} = \f{2}{1-v}\]Solving for \(t\):

\[t_{b} = \f{2v}{(1-v)(1+v)} = \f{2v}{(1-v^2)}\] \[x_{b} = \f{2}{1-v^{2}}\]\(x_{b}\) differs from \(t_{b}\) a factor of \(v\). The slope of the line is then \(t = vx\) which is symmetric about the light ray with \(x = vt\).

We know that \(x' = 0\) when \(x = vt\), so we write:

\(x' = x - vt\) (this is simply the Galillean transformation for the \(x\) coordinate, setting \(x=vt\) gives \(0\))

As stated before this transformation is incorrect, so we introduce some factor \(f\) that could depend on the velocity between the two reference frames:

\[x' = (x-vt) f(v)\]Similarly, when \(t = xv\) , \(t'= 0\), so we introduce some function \(g\) that depends on \(v\):

\[t' = (t - xv) g(v)\]To satisfy the second postulate which state that the light ray should have the same velocity between the stationary and moving frame.

Assume \(x=t\), then it must also be true that \(x'=t'\). This implies that out velocity dependent functions are equal:

\[f(v) = g(v)\]We rewrite the equations in terms of \(f(v)\) and in terms of the relative velocity (essentially solving for \(x\) and \(t\) which allows us to find the transformation “correction”.

\[x = (x' + vt') f(v)\] \[t = (t'+ x'v) f(v)\]By brute force, we plug in out prime definitions, \(x'\) and \(t'\), into the equation for \(x\) above:

\[x = [(x -vt) f(v) + v ( t - xv) f(v) ] f(v)\] \[x = (x-vt) f(v)^{2} + v (t - xv) f(v)^{2}\]After some algebra, solving for \(f(v)\), we find that

\[f(v) = \f{1}{\sqrt{1-v^{2}}}\]Now we can plug this into \(x'\) and \(t'\):

\[x' = \f{(x - vt)}{\sqrt{1-v^{2}}}\] \[t' = \f{(t-xv)}{\sqrt{1-v^{2}}}\]and of course to make these equations dimensionally consistent, we divide \(v^{2}\) by \(c\):

\[x' = \f{(x - vt)}{\sqrt{1- \f{v^{2}}{c^{2}}}}\]and for \(t'\):

\[t' = \f{(t-x\f{v}{c^{2}})}{\sqrt{1- \f{v^{2}}{c^{2}}}}\]In an inertial frame \(S\), a four vector is defined as a set of four numbers \(A = (A_{1}, A_{2}, A_{3}, A_{4})\). A transformation between frame \(S\) and \(S'\) can be expressed as \(A' = \Lambda A\), where \(\Lambda\) is the Lorrentz transformation between \(S\) and \(S'\).

[1] http://physics.mq.edu.au/~jcresser/Phys378/LectureNotes/VectorsTensorsSR.pdf